It’s the biggest bike firm in the world (still, just), and Honda has a solid claim to being the best. It wins MotoGP titles with impressive regularity, but also sells 50cc scooters by the million in developing markets. It’s got the largest dealer network in the UK, and a Honda dealer can sell you anything from a Cub scooter right up to a GL1800 Gold Wing, 214bhp Fireblade, Africa Twin adventure tourer or a full-bore 450 motocross machine.

Honda’s also come up with some amazing bikes down the years too. Genuine game-changers, like the CBR900RR FireBlade of 1992 and the 1969 CB750 superbike, as well as mundane transport like the C90. It’s also produced its share of pure exotica, like the RC30 homologated World Superbike racer for the road.

Picking ten of the best to write about here is one of the hardest jobs you could think of for a bike journalist. And we’re missing so many epic bikes: the jewel-like two-stroke racer NSR250, the RCV213 S road-going MotoGP rep, the oval-piston 32-valve NR750 and the mythical RC45 superbike. Is there a Honda that you reckon deserves its place before any of these? Shout up and let us know – and maybe we’ll do the best of the rest another time…

CB750

To modern eyes, the original Honda CB750 doesn’t look like anything particularly special. Disc brakes, an inline-four engine with electric start making around 70bhp, and a standard naked design; it’s all pretty mundane in 2021. But in 1969, all of this stuff was completely revolutionary. Back then, almost all bikes had one or two cylinders, drum brakes and kick start – and 50bhp was a mind-blowing amount of power. The CB750 was a massive leap forward, perhaps the biggest in motorcycle design since the first internal combustion engines were bolted onto bicycle frames at the end of the 19th century.

Riding a bike like this nowadays is at once humdrum and exhilarating. The performance is almost dull, certainly compared with what a 750cc machine should be like today. The engine is low-revving, power rises sedately, and the chassis is only just up to handling it. Brakes in particular have come on massively in the last fifty years, and you’ll need to plan your stopping well in advance.

But on the other hand, the CB750 is such a piece of motorcycle mythology that it’s a pleasure just to be on one. The engine might be light on grunt but it’s smooth, clean, and what power it has is delivered in a very pleasing fashion. And it’s clearly a part of the modern world, rather than something from a completely different time – you have electric start, decent controls, proper instruments, and things like the gearshift are in the correct place for a 21st century rider. Later versions gained DOHC heads, fairings, air suspension and the like, but the competition had caught up, and the later CB750s didn’t have the same success.

The CB750’s real impact lies in its influence on the path of motorcycle development though. The across-the-frame engine layout with steel tube cradle frame, twin-shock swingarm, disc brakes and four-cylinder powerplant all became standard across the whole Japanese sector through the 1970s and 80s.

Even when engines became water-cooled and frames switched to aluminium castings and extrusions, that essential design remained the same. Eventually, full fairings, monoshock rear suspension and alternative engine layouts became widespread – but the whole motorcycle world still owes a lot to Honda’s original superbike.

Gold Wing

The Honda GL1800 Gold Wing is an incredible piece of engineering. The first time you see one in the flesh, it’s a bit of a shock just how big it is – and how much stuff there is on it. The latest Wing uses a flat-six cylinder motor with reverse gear, built-in sat nav and sound system, integrated luggage and super-comfy rider and pillion accommodation.

But the original was quite different. Launched in 1974 as the GL1000, it was a naked machine with no fairing at all, and a flat-four 999cc engine. That motor made it the ‘hyperbike’ of its day – most full-bore four-stroke machines were 750s or 900s, so a full litre-class capacity was unusual. But there were some important design choices that put it in the ‘grand touring’ class, especially the shaft final drive.

Nowadays, shaft-drive is an efficient, well-developed choice, with cunning linkages to reduce the impact of a shaft on chassis performance. But in the early 1970s a shaft drive meant extra weight and quirky handling compared with a chain and sprockets.

The naked 1000 was a big hit, especially in the US where its large motor and relaxed touring manners were at their best. It grew in capacity to an 1100 in 1979, but it was the Interstate version in 1980 which showed the Gold Wing’s true pathway.

The Interstate was a factory-ready mega-tourer, with massive barn-door fairing, luggage and super-luxury seating for two. There had been loads of aftermarket fairing options for the Gold Wing through the 1970s, but Honda finally offered an integrated turnkey option, and the Interstate quickly gained legendary status. While most bikes didn’t even offer a windscreen, the Wing had options for a stereo, a CB radio, on-board compressor for the air-adjustable suspension plus full pannier and top case luggage.

The GL1200 version added more capacity, power and torque, plus even more luxury kit, but it was the GL1500 in 1987 which took the next big step, up to a flat-six engine, 100bhp, reverse gear and spaceship styling and equipment levels.

Honda was in its pomp in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and nothing could come near the 1500 Wing for sophistication and design. The fifth generation Wing jumped to a staggering 1,832cc capacity in 2001, while Honda also improved the handling massively by moving to a much stiffer aluminium frame and uprated suspension and brake components.

Now, in 2021, the Gold Wing is on its sixth generation. The engine is still an 1,832cc flat six, but with a totally redesigned four-valve-per-cylinder layout, 125bhp output and much improved fuel consumption and emissions. Honda had discontinued the Pan European tourer, leaving a gap for a slightly smaller tourer, so the Gold Wing actually shrank a little in terms of size and mass, making it more manageable and improving the handling.

A Dual Clutch Transmission auto-box was an option, and Honda also trialled an all-new front suspension system, using a double wishbone monoshock setup.

Nearly fifty years from the first GL1000 then, the Gold Wing is still an incredible piece of engineering – and also an amazing bike to look at and ride.

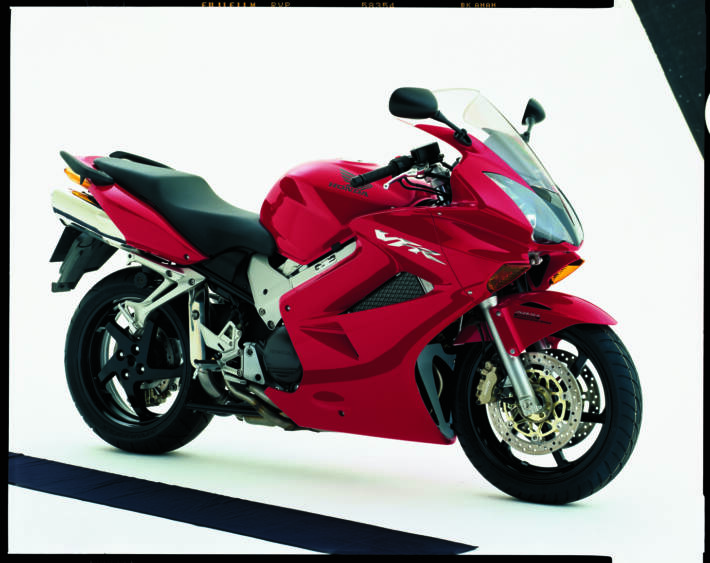

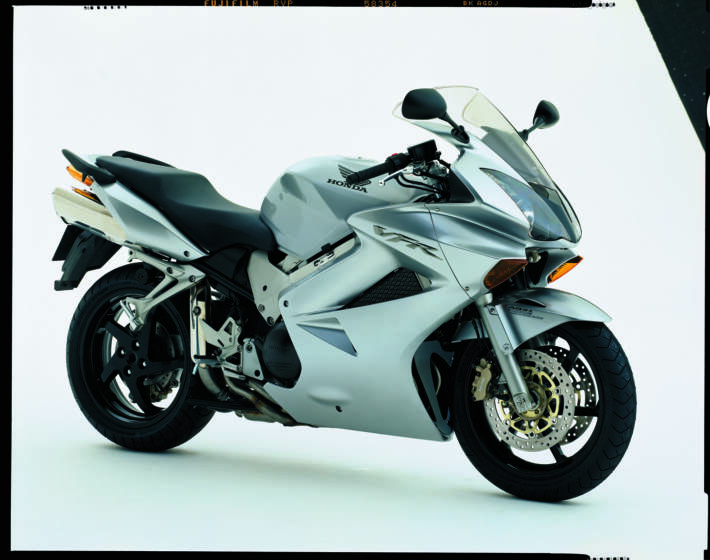

VFR750/800 F

Honda’s first attempt at a 750cc V-four engine wasn’t its best work to be fair. The VF750 motor was used in various machines in the early 1980s, including the US-market Sabre and Magna cruisers, and the VF750F Interceptor sportsbike, but suffered various engine failures in service. The camshafts and cam chain drive were particular areas of concern, with valve train problems plaguing the normally-reliable Hondas.

Back to the drawing board then, and a total redesign of the cams and drive system led to the new VFR750 engine: Honda replaced the chains with a super high-quality gear drive system, giving total reliability and a new bullet-proof reputation for the 750 V-four layout. But Honda didn’t stop at the engine.

The new lump was bolted into a cutting-edge sporty chassis, with aluminium frame and swingarm, high performance brakes and suspension, plus a full fairing, giving us the 1986 VFR750F. The power output was up by more than 20bhp to 104bhp, mass was down by around 20kg, and the overall package was a fantastic road-biased sportsbike. It was much less of a race-replica than the Suzuki GSX-R750, and more on par with the Kawasaki GPX750 and Yamaha FZ750.

As the years passed though, the 750 class went in a much more hardcore direction generally, with Kawasaki bringing out the ZXR750, and Yamaha dropping the FZ in favour of the limited-production homologation special FZR750R OW01 superbike. Honda released its own megabucks race-replica, the VFR750R RC30 (see below), but rather than dropping the ‘F’ model VFR, it cleverly moved it sideways.

The 1990 model gained a single-sided swingarm and a load of chassis and engine refinements, making it more of a sport-touring machine. Between 1990 and 1998 the VFR750 was the class leader when it came to high-performance, well-built practical sports-tourers.

1998 saw a new VFR800 with larger capacity fuel-injected engine based on the motor from the RC45 superbike. It was broadly similar in terms of performance and equipment – showing how good a job Honda did with the original version. Indeed, the VFR800F remains in production in 2021, alongside the VFR-based Crossrunner 800.

Honda CBR900 RR FireBlade

In much the same way as the CB750, the original FireBlade transformed motorcycle design, while making a significant leap forward in terms of performance. Perhaps surprisingly though, there was little in the way of all-new advanced technology.

For a 1992 machine, the CBR900RR spec sheet contained nothing earth-shattering: a water-cooled 16-valve inline-four four-stroke engine, in a twin-beam aluminium frame, with monoshock rear suspension, full fairing, and disc brakes all round. That describes a host of sporting machinery from that era: the Yamaha FZR1000R EXUP, the Kawasaki ZZ-R1100 and 600, and (with a slightly different frame layout) Suzuki’s GSX-R750 and 1100s.

So what was the difference with the FireBlade? Well, for the first time, a bike designer – the legendary Tadao Baba – had made a big effort to cut mass, and focus on usable, controllable performance – ‘Total Control’ as it was dubbed. Where other firms were piling in with bigger engines making ever more power, while overall mass crept upwards, Baba stuck with a smaller 893cc capacity and a decent 122bhp claimed power.

Best of all though, he managed to keep the dry weight down to a stunning 185kg – 35-45kg less than the litre bike competition.

Honda had managed all this without using exotic materials – no carbon fibre or titanium components – and by simple, clever design. Less is definitely more with the CBR900RR – look through the frame, behind the engine and there are large spaces with nothing there. Optimising the chassis and engine together as a package reaped enormous benefits in terms of handling on road and track, and the performance was sublime.

Over the next five years, the FireBlade evolved into a mature, effective design, but by 1998 the new Yamaha YZF-R1 had appeared and beat Honda at its own game. A full 999cc engine made more power, and an even lighter chassis design toppled the Blade as king of the litre-class sportsbikes.

Honda came back with bigger ‘Blades – first 929cc then 954cc, with PGM-FI fuel injection and even sharper chassis. The 2002 CBR954RR was the lightest of the FireBlades at just 168kg dry, and is now much sought-after as the last of the old generation bikes, before the all-new CBR1000RR Fireblade appeared in 2004.

Honda CBR600F

It might be hard to believe now, but 600cc sportsbikes used to be the biggest selling bikes around. From the mid 1980s to the mid-2000s, especially in the UK, people couldn’t get enough of them. The big four Japanese firms all built excellent inline-four 599cc motors, bolted into sporty chassis, and used in the 600 Supersport race classes. Triumph even joined in for a while, with its TT600 and Daytona 600/650 supersports machines.

Arguably the archetypical 600 was Honda’s CBR600F though. It first appeared in 1987, taking over from the old-tech CBX550 air-cooled machine. This was a common pathway in fact: Kawasaki replaced its GPz550 air-cooled sportster with the water-cooled GPZ600R, and Yamaha did the same with its FZ600 and FZR600 replacement.

But the CBR600F had nothing to do with the elderly 550: it had an all-new water-cooled 16-valve engine making around 85bhp, in a lightweight steel frame, hidden by all-enclosing plastic bodywork. Dry weight was impressive at 180kg, and while the suspension, brakes and wheels were on the sporty side, the CBR used fairly standard components.

On paper then, it was a steady piece of kit. But on the road the CBR600F was a revelation, and far more than the sum of its parts. There was an integrated feel to the design and the performance – and it even did well in racing. The engine was super-reliable, and tuners could get very decent power out of it too.

The slightly staid steel-framed road bike showed fancier bikes how to do it at race tracks all round the world all through the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Honda was slow to bring in fundamental tech updates – an aluminium frame didn’t appear until 1999, and fuel injection only showed in 2001. And by then the Kawasaki ZX-636R, Yamaha YZF-R6 and Suzuki GSX-R600 had bested it in terms of track performance. By 2003 though, Honda had replaced the CBR600F with an all-new CBR600RR, which was much sportier.

The RR was far better on track – but it did lose a lot of the all-round capability that the F had displayed for nearly two decades. Indeed, Honda brought the CBR600F name back in 2011, in the form of a fully-faired version of the CB600F Hornet.

VFR800X Crossrunner

One of Honda’s biggest strengths is its ability to build a bike which is far more than the sum of its parts. And the Crossrunner is a great example of this. On paper, it’s about the laziest thing you could imagine: the firm took the venerable VFR800 engine and frame, added some longer-travel suspension and adventure-lite touring bodywork, before launching it upon an unsuspecting market in 2011.

Pundits scoffed at the Crossrunner – it didn’t seem to fit in anywhere, being heavier and pricier than twin-cylinder options like the BMW F800 GS, and with hardly any genuine off-road abilities.

But once you jump on, all that scepticism disappears. The engine is brilliant: the 98bhp VTEC-equipped V-four 782cc lump has fabulous drive low-down, and when the variable-valve setup kicks in (switching from two to four valves operating per cylinder) you get a real kick in the pants at the top end.

The sound is glorious from the rider’s seat, especially with the optional-fit Akrapovic end can, and the only downside is the fuel consumption, which is good when you go steady, but falls off a cliff when you give it big handfuls.

The chassis is just as pleasing. The riding position is comfy and relaxed, though the seat gets a bit hard on really long rides, and the screen gives good weather protection. Brakes and suspension are a little on the soft side, but for a road-biased soft-ish ADV machine, it’s more than up to a bit of a back-road hustle.

The 2015 update focussed on chassis and braking upgrades, and sharpened the handling up a treat. Honda also redesigned the bodywork for massively improved looks and added details like LED lighting. Later models got an adjustable screen and 12v power socket too.

Africa Twin

Like the Gold Wing and the FireBlade, the Africa Twin (AT) is one of Honda’s most legendary names. But it disappeared for a long time in the early part of the 21st century. The original AT was the super-rare XRV650 sold from 1988-89, before being replaced by a 750 version from 1990-2003. The first generation used a narrow-angle 52° V-twin engine, with SOHC three-valve heads, making 57bhp in 650 form and 62bhp for the 742cc 750.

That slim powerplant was bolted into a steel tube cradle frame with hardcore Paris-Dakar race styled bodywork and paint, long-travel suspension, 21” front wheel and a beefy aluminium bash plate protecting the sump.

The 750 Africa Twin was a big hit in continental Europe, but UK riders were less keen. Sportsbikes ruled the market at the time, and punters preferred to get 115bhp in something like a Kawasaki ZXR750 if they were paying the insurance and running costs of a 750cc machine. By 2003, then, it was rare to see a new XRV750 being ridden off a dealer’s forecourt.

Fast forward to 2016 though, and the time was ripe for the Africa Twin to return. Big adventure-styled machines were all the rage, and used XRVs were being snapped up by hipsters and collectors alike. Honda did the right thing though, and came up with an all-new model to fill the gap in its range – the CRF1000L Africa Twin.

It switched from a V-twin to a parallel twin, added 250cc, and came with bang-up-to-date chassis design and technology. It also looked great, especially in the classic Honda red/white/blue paint schemes.

In some ways the 1000 AT actually created its own light-heavyweight class when launched. Bikes like the BMW F800 GS and Suzuki V-Strom 650 had covered the middleweight class, then there was a bit of a jump to the likes of the BMW R1200 GS and Triumph Tiger. The Honda was right in the middle though – the 998cc motor made 94bhp and overall kerb weight was 230kg ready-to-ride.

There was a bit of criticism over the power output though, and Honda gave in for 2020, bumping capacity up to 1,084cc, with a true 100bhp and much more grunt. There were loads of detail upgrades and chassis sharpening too, and the 2020-on bikes are genuinely ace bikes to ride and use – more than living up to that legendary moniker.

Super Cub

Most of the bikes in this list are top-end, high-performance machines, with fire-breathing performance and cutting-edge technology. But a firm like Honda didn’t become the size it is by concentrating solely on that sector of the market. Indeed, the firm’s foundations are built on much more prosaic designs – like the Super Cub and its variants. First built in the 1950s, the single-cylinder air-cooled steel-framed Super Cub has evolved from 49cc up to 125cc, with stops at 70, 90 and 110cc along the way.

The original 49cc C100/C50 model sold in its millions, giving affordable mobility to a whole generation of people around the world. In developing economies, it was a pure workhorse, transporting workers and goods, while in countries like the UK it gave freedom to youngsters and helped commuters escape indifferent public transport options.

Honda’s trick was to make a bike that was easy to use, with the semi-automatic transmission, easy to repair with basic tools, and super-reliable to start with. Where European firms were selling unreliable, rust-prone bikes with dreadful electrics, the Super Cub just worked, virtually every time. The four-stroke engine was almost over-engineered, and would keep running even under virtually non-existent backyard maintenance regimes.

Honda even came out with an overhead camshaft engine for the C90 version in the mid-1960s at a time when all but the most exotic full-bore motorbikes used the more basic overhead valve pushrod layout.

You can still buy a Super Cub from your local Honda dealer now, with the latest C125 version boasting a super-clean, fuel-injected 125cc motor, nine horsepower, and the classic four-speed gearbox with auto-clutch. It’s nowhere near as important for Honda as the very first model – but still drives the economies of much of the world.

And it’s a nice touch that the firm has kept the faith with such a legendary part of its two-wheeled history.

RC30

Honda has factory code-names for all of its bikes. An RC29 is a Honda Shadow VT750 cruiser. The RC31 is the NT650 Hawk/Bros roadster. The RC80 is the VFR800X Crossrunner. Very few of these names stick – but the RC30 is perhaps the most famous.

It’s the code for the VFR750R superbike homologation model, which transformed the 750 class in 1987 when it first appeared. It took the outer cases for the standard VFR750F, modified them to suit and crammed in a load of high-end race components, including titanium con-rods and forged two-ring pistons. The crank phasing changed to a big-bang 360° layout and parts like the cam-gear drive were works of art, adding to the very serious investment in this high-end race motor.

It even came with a slipper clutch, long before they were fashionable.

The engine made around 118bhp as standard – but the real point of the expensive innards was to allow race teams and tuners to extract much more power and revs for the track. Race bikes made closer to 140bhp by the end of the RC30’s development – heady stuff for a 750 in the early 1990s.

The chassis was less flash than the motor, which is often the case with race homologation models. Most classes allow suspension, wheel and brake changes, so the stock stuff will end up being removed before testing anyway. Parts like the aluminium frame and single-sided swingarm got plenty of attention though, as did the fibreglass bodywork panels and lightweight aluminium fuel tank.

Obviously, all this kit meant a stiff price tag. A new Honda RC30 cost £10,599 in the UK in October 1988 – equivalent to £24,750 in 2021. For comparison, a standard VFR750F was around £5,799 in the late 1980s, and a Kawasaki ZXR750 H2 cost £5,549 when launched in 1990.

The RC30 was replaced by the similarly-exotic and expensive RC45 in 1994. It boasted fuel injection – virtual science fiction on a race bike at the time – an all-new engine and even more stunning performance. Like all the 750cc fours though, it struggled in WSBK and BSB racing: the rules seemingly favouring the 1000cc V-twins of Ducati.

Honda did win a WSBK title with the RC45 in 1997 under John Kocinski – but it gave in eventually, replacing the RC45 and its V-four race lineage with the VTR1000 SP-1 V-twin for 1999.

CBR1100 XX Super Blackbird

In hindsight, it’s amazing that Honda ever made this bike. With eco-friendly, soft-edged 2021 sensibilities, making a bike that is so obviously about 200mph straight-line speed potential is just mind-blowing. As was the performance of the Honda CBR1100 XX Super Blackbird at the time.

Launched in late 1996, the Blackbird’s name was, reputedly, homage to the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird Mach 3+ spy plane – the fastest, highest-flying thing in the sky right up until the end of the 20th century.

Wherever the name came from, it was aimed right at Kawasaki’s ZZ-R1100 hyper-sports tourer, with power, weight and tech all designed to topple the ZZ-R’s top-speed crown. Kawasaki had held the ‘fastest bike’ title for much of the modern era, with its Z1, Z1000, GPz1100, GPZ900R, GPZ1000RX and ZX-10 all at or near the top.

But the new Honda easily swept the elderly ZZ-R aside. It had much more power – 160bhp – from its FireBlade-derived engine design, and was a few kilos lighter too, at just 223kg claimed dry mass. There wasn’t anything radical about the engineering – the motor was a conventional inline-four with a 16-valve head, 1,137cc capacity, water-cooling and four carburettors, and the chassis used a standard twin-spar aluminium frame with dual-sided swingarm and conventional forks.

Honda did fit its CBS combined braking system though, which linked the front and rear brake circuits for improved braking safety and stability – and the engine featured dual balancer shafts for extra smooth running.

The big speed feature was arguably the aerodynamic bodywork though. The slippery fairing let the big Honda slice through the air with ease, cocooning the rider in a bubble of (mostly) still air. The top speed was impressive of course, but the CBR1100’s real success lay in its refinement.

It was a proper luxury express, with the smooth engine, comfy riding position, excellent wind protection and high-quality Honda build making it a lovely place to be. The speed meant you could cross countries with ease, and it was good two-up as well. Add some hard luggage and you had excellent high-speed transport.

The first model wasn’t perfect, with an annoying flat spot in the power delivery. That was sorted with the later 1998 version though, which used Honda’s PGM-FI fuel injection system, improving economy, reducing emissions and smoothing out the power.

Honda also added a new sealed ram-air intake system, with dual air intakes under the headlight feeding the motor with masses of cool, high-pressure air – just the job for maximising output at maximum speed.

13 comments on “Top Ten Honda Road Bikes of All Time”

Unfortunately you missed out a bike that is still revered by many today, the Pan European.

What about the cd175 from the 70s

You missed the iconic (well before it’s time) Honda CB1100X11 Blackbird engine in a naked form. Superb bike which will still stick with modern day bikes.

I believe they pulled the plug due to the press not liking it, if it was brought out today no one would bat an eyelid.

Don’t forget the Honda 400/4 superb bike in its time, & still is

Agree with you there. Had a yellow F2 model.

Love my CB1100 2015 model, it’s sex on wheels.

Erm! CBX! The most charismatic engine ever to come out of Japan.

Or the first homologation special the

CB1100R

I liked the CB1100R

You missed a great range called the XR models and in particular the 500.

The cb1100rc is my favourite

I’d of thought the Superdream would have got a mention.

What about the CB500, what a great all rounder.

Very much over looked, by everyone.

You forgot the XBR 500 , the best single cylinder engine to come out of Japan . My current one has over 215,000 trouble free miles on it and I have owned it for 28 years .