If you’re a fan of posh, exotic motorcycles, then Italy won’t be far from your heart. Sure, there have been super high-tech machines from other parts of the world: Honda in Japan produced the likes of the NR750 and RC213V-S, BMW built the superlative HP4 Race ultra-superbike, and there have been bikes like the Confederate Wraith from the US and Norton’s V4 SS from the UK.

But, as with the car world, it’s the factories of northern Italy which consistently produce the sauciest of two-wheeled kit. Of course, there’s the big firms: Ducati as part of the Volkswagen-Audi Group and Aprilia from the giant Piaggio conglomerate, and both of them turn out the most glamorous high-performance kit every year.

Then there’s MV Agusta, on a smaller level, but still working away. And on an even more exclusive scale are superbikes from the likes of Bimota, Benelli and Mondial, which have had their struggles in terms of financial backing and business setup – but have turned out some remarkable bikes over the past couple of decades.

Bimota is now part-owned by Kawasaki, and is aiming to re-package engines and other parts from Japan with its own Italian chassis and styling designs. Benelli is owned by Chinese firm Quianjiang, while Mondial has a relationship with Piaggio, also in China. Both of them have moved away from exotica for the moment, turning out small-bore scooters and commuters that have kept them alive, with the odd larger machine appearing along the way.

But the exotic superbikes they’ve built , and their two-wheeled heritage, marks them out as a little bit special. Here’s our pick of the best exotic Italian superbikes from the 21st century, so far.

Aprilia RSV Mille

It’s hard to believe now, but before the 1998 RSV Mille appeared, Aprilia was a small bike specialist. Its RS250 two-stroke race-replica repackaged the Suzuki RGV250 V-twin engine in a sharp supersports package, and its biggest machines were a couple of 600cc single-cylinder dirtbikes, the Tuareg and Pegaso. It had masses of race success, especially in the 125GP and 250GP classes, as well as off-road, but hadn’t taken the jump to large-bore road bike production pioneered decades earlier by Ducati.

The RSV Mille changed all that though. Using an all-new 998cc 60° V-twin engine from its powertrain partner Rotax, it instantly gave the Noale firm a competitive litre-twin road bike that could go up against Ducati’s legendary 916 superbike – and even the Japanese 900-1000cc fours of the time.

The engine was a peach: twin-plug four-valve heads, DOHC, water-cooling, fuel-injection, and it put out a very healthy claimed 128bhp. The chassis actually looked more like contemporary Japanese design tech: it had a twin-spar aluminium frame and dual-sided fabricated alloy swingarm, with Showa forks. The brakes and rear shock were European though: Brembo and Sachs parts, and it weighed in at a decent 189kg dry.

That original RSV was a big hit for the firm, and a strong contender in the 1,000cc V-twin class built by Ducati. Suzuki’s TL1000 and Honda’s VTR1000 ranges matched or slightly beat the RSV on paper, but the Aprilia had a solid mix of Japanese and Italian influences. It was definitely the most ‘Japanese’ of the Italian superbikes of the time, with more practicality and usability. It had some reliability woes, but was generally a well-built, efficient and trustworthy machine.

When it comes to pure exotica, the RSV Mille is a great entry point. Early models are cheap now, and if you’re willing to get involved with the intricacies of ownership, will make a great everyday Italian retro superbike. Later, the firm brought out a variety of posh variants, including the 1999 ‘R’ version, which added forged Oz wheels and full Öhlins suspension setups to a single-seat chassis with some carbon fibre bodywork.

After redesigns in 2001 and 2003, ‘Factory’ and ‘R’ versions were released, again with higher-spec chassis kit and more power. Special limited editions followed, including sweet Colin Edwards and Noriyuki Haga WSBK replicas in 2002 and 2003, and the Nera edition in 2004, all with higher-spec running gear, carbon parts, more engine power and track-ready add-ons, like race ECUs and titanium exhausts.

The most exotic RSV Mille is the SP version, built in very limited numbers. Just 150 were produced in 1999, to homologate the RSV for WSBK racing with Peter Goddard riding in the first season. It’s a completely different machine: the 145bhp motor had a shorter 63.4mm stroke and bigger 100mm bore, 996cc capacity, single spark plug for bigger valves and a host of other mods to make it better suited to race tuning.

The frame had full adjustability for engine mounts, swingarm pivot and steering head angle, and was stiffer than the stock bike’s unit. Full carbon bodywork and Öhlins race suspension front and rear rounded off the fine spec – but from a distance it was hard to tell the SP from a standard RSV Mille.

The dual silencer cans were the main clue that you were looking at one of the rarest Italian superbikes ever made – not one of the most common…

Aprilia RSV4

By the middle of the 2000s, Aprilia’s RSV V-twin was getting pretty long in the tooth. Where Ducati was able to extend the capacity of its big superbike twin motor right up to 1,099cc then 1,198cc and beyond, the RSV Mille couldn’t go any bigger without starting over with a new engine. And since the WSBK rules had changed in 2003, allowing four-cylinder 999cc machinery, why stick with the twin cylinder layout if you don’t have to? Ducati was wedded to the 90° V-twin in a way Aprilia just wasn’t – and the Noale firm took the chance for a rethink.

The result was the 2009 RSV4, an all-new 65° V-four 999cc engine, making 180bhp, in a super-compact aluminium twin-spar chassis, with high-end running gear and sweet styling. It had elements of the old RSV twin in the overall looks, but was a much sharper, more modern design. It found success on the track fast: taking the WSBK title in 2010 under Max Biaggi. And it was a success in the showroom too. Despite being focused on track performance, it worked well on the road, with superlative performance, and cutting-edge electronic riding aids for the era.

It took Aprilia’s superbike offering up to a new level compared with the twin-cylinder RSV, and was much more of a match for Ducati in terms of technology, design, performance and exoticism. The engine used ride by wire fuel injection, dual injectors per cylinder, variable inlet trumpets, and was extremely compact thanks to the narrow 65° V-angle.

That V-four engine soon appeared in a new Tuono super-naked machine, and then was increased in capacity to 1,077cc in the Tuono 1100 of 2015. The RSV4 stuck with the 999cc capacity until 2019, when it followed Ducati’s Panigale V4 in moving to the larger 1100 engine. The RSV4 1100 Factory had an even higher output version of the engine, now making 217bhp, besting even the Panigale, and was a total monster to ride.

And if that’s not exotic enough for you, Aprilia also launched a limited edition X version, with a track-only design, race-tuned motor and super-light chassis. The numbers are stark: 225bhp and 165kg dry, but they came at a price. Only ten were available, costing nearly 40,000 Euros each, and all sold out within seconds online. With a host of unique features: a ‘no-neutral’ gearbox, with neutral gear below first, for seamless shifting, Brembo GP4-MS race calipers, hand-built engine with race cams, forged magnesium wheels, full titanium Akrapovic exhaust and much more, the RSV4 X really is an incredible piece of work.

Benelli Tornado Tre 900

Launched at the start of this century, the Benelli Tornado created a huge stir as soon as the first pics were released in 2002. Here was a bike with an all-new engine layout – a high-tech 900cc triple – and a super-trick chassis setup, but it also had some totally unique design ideas.

The most striking one was at the back end: rather than use a conventional front-mounted water cooling radiator, the Tornado located its cooling system under the rider’s seat, with aerodynamically crafted ducts leading high-pressure air from the front of the bike into a sealed conduit that held the radiator.

Part of the design was a pair of electric fans inside the tail unit, just above the rear tyre, which provided cooling air flow when the bike was static or moving slowly. The radical design made a lot of sense on paper: it removed the massive drag from having a big flat radiator facing the front of the bike, and the careful design of the air channels allowed a smaller radiator to be used, saving some weight.

The rest of the Tornado was a little more conventional. The main frame used a composite design, with steel tubes and aluminium plates, plus an asymmetric swingarm design, and the three- cylinder engine was a stressed member, adding stiffness to the chassis. Suspension was by Marzocchi, though the high-end LE race version used Öhlins forks and shocks, and brakes were Brembo race calipers and 320mm discs up front.

The bodywork was actually designed by a British stylist, Adrian Morton, rather than some Latin maestro. Morton had studied under Massimo Tamburini at the Cagiva design department, and would go on to design high-end machines for MV Agusta, including the current Rush super-naked.

When launched, the Tornado suffered a bit from lack of development. The fuel injection was by French firm SAGEM (who made the injection for early Triumph bikes), and the throttle response and ridability was poor on initial production models. That improved over time, as did the reliability of the engine itself.

Later, Benelli increased the stroke of its 898cc triple, giving a 1,131cc capacity, which featured first in its TNT supernaked, and found its way into the final versions of the Tornado too. The Benelli company had a hard time financially though, with Chinese firm Qianjiang taking over in 2005. The Tornado stayed in production until the early 2010s, with the last models selling at a massive discount in 2014. Prices are on the way back up now though, with the unusual, one-off design making it a really interesting Italian exotic machine.

Bimota Tesi 3D

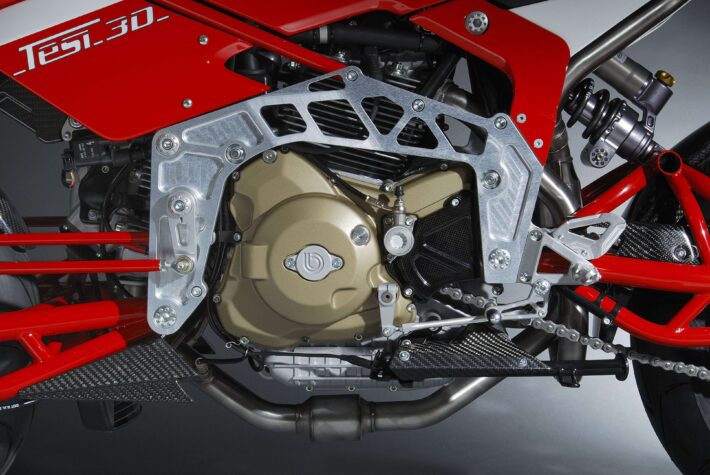

‘Tesi’ is Italian for ‘thesis’, but it’s also the name of a Bimota motorcycle concept which dates back to the 1990s. That moniker comes from the origins of the unique chassis design: a university thesis on a motorcycle engineering project by Pierluigi Marconi and Roberto Ungolini, who went on to work at Bimota. The heart of the design is the so-called hub-centre steering front-end.

Rather than have the front wheel attached to the frame by a pair of telescopic forks, it’s held by a front swingarm, just like a conventional rear suspension system, with a monoshock to absorb bumps. The steering function happens inside the hub of the wheel – the ‘hub center’ – with linkages controlling the wheel position attached to the handlebars. The swingarm is wide enough for the wheel to turn from side to side, not as much as with a conventional steering head, but enough to work as a superbike chassis.

Away from the front end, the chassis is simply a pair of super-stiff horseshoe-shaped plates either side of the engine, which link the front and rear swingarms, and mount onto the crankcases.

The result looks very weird, but worked as planned. The idea is to separate the braking and suspension forces at the front end: when you brake, the forces go straight from the tyre through the swingarm into the main frame, rather than through a set of fork springs.

The original Tesi prototypes were built on a range of engines, including a Kawasaki GPz550 and Honda V-four 400 and 750 motors. But the first production bikes in 1991 used Ducati 851 superbike engines, later increased to 904cc capacity. Over the intervening years, Bimota has had some serious financial woes, and the Tesi came and went, with various re-designs, and powered by other Ducati engines. A rival company appeared, Vyrus, which produced its own take on the Tesi theme.

Now, with Kawasaki taking a share of ownership in Bimota, its Tesi has been redesigned once more, to use the Japanese firm’s H2 supercharged inline-four engine. It claims to make 231bhp, weighs 207kg dry, and costs 64,000 Euros – proper exotic numbers…

Ducati 748 R

No list of Italian exotica would be complete without one of Ducati’s 1990s superbikes – the 916 or 748 family. We’ve plumped for the 748 R here, as one of the rarest, poshest and most evocative of the range.

The 748 first appeared a year after the 916, in 1994, and offered a supersport-compliant V-twin to go against the 599cc inline-fours from Japan. It looked identical to the 916, with the same gorgeous bodywork and chassis design, with just graphics and a slightly narrower rear tyre to tell them apart.

The motor used the same 90° V-twin eight-valve desmodromic design as the 916, with narrower 88mm bore and shorter 61.5mm stroke, for the 748cc capacity. Coincidentally, the very first prototype 8-valve desmodromic V-twin engine developed by the firm was also a 748cc unit, which gives a nice symmetry with the 748.

By the time the 748 R was launched in 2000, the engine had been developed to make 106bhp, 20bhp more than the original bike, thanks to the race-ready tuning parts fitted by the Borgo Panigale outfit. The R engine had titanium con-rods and valves – common now, but very unusual back then – as well as massive inlet ports and dual injectors per cylinder, including a race-type ‘shower’ injector firing straight down the centre of the intake port.

The basic 748 chassis is trick enough, with the steel tube trellis type frame and single-sided rear swingarm. On the R though, things were cranked up a notch, with Öhlins race suspension front and rear, Marchesini forged wheels and Brembo four-piston brakes with 320mm discs up front.

The point was to compete in World and British supersport racing, but even this trickest of 748 models struggled in competition. The inline-fours from Japan (and later from Triumph in the UK) could easily make well over 120bhp peak power, while the 748cc V-twin needed a lot of very expensive tuning to get anywhere near 120 horses.

Race teams are generally cash-strapped, especially in supersport racing, and there was much more bang for your buck with a 599cc four. Ducati took one WSS title in 1997, with Paolo Casoli riding, and one British Supersport crown in 2002, with Scots rider Stuart Easton onboard the Paul Bird Motorsport 748 RS (a factory race version of the 748R).

Ducati 999 R

Ducati was up against it when it had to finally replace the legendary 916 series superbike. The engine had grown to 998cc, and the chassis had been refined, but the firm needed a new platform to take its V-twin range to the next level.

But how do you follow-up on one of the most amazing bikes ever built? Well, the Bologna firm bit the bullet, and launched something very different: the 999, penned by South African designer Pierre Terblanche. Nowhere near the 916 in terms of what you might call ‘conventional beauty’, the 999 was a controversial design from the off. Its vertical stacked headlights and flat, broad, side fairing panels were the polar opposite of the sinuous bodywork on the Tamburini-designed machine.

But on the other hand, the chassis and engine technology had moved on from the late-1980s foundations of the 916. We still got a 998cc 90° V-twin with eight valves, desmodromic operation, fuel injection and a strong, torquey power output (around 125bhp on the first base model 999 in 2003) – which was at the top of what the old 916 range could muster. Indeed, the base 999 used the same basic Testastretta engine design used on the 998, with further development.

The chassis had also evolved, with a longer, dual-sided swingarm that helped save weight and improve handling. The frame remained as a steel tube trellis design, and as with previous Ducatis, the entry level models used Showa suspension, with Öhlins shocks and forks on the higher-spec variants.

When it comes to Italian exotica picks, the base 999 and mid-range 999 S models probably come second to a nice late 998 R or 996 R. But we’re looking at the 999 R here, which took Terblanche’s machine to new levels. It got a proper 999cc race-ready engine with enormous 104mm pistons and loads of titanium internal parts, that made 150bhp out of the crate, and stomped all over the old engine.

That behemoth of an engine lives in a revised steel trellis frame with adjustable geometry, and suspended via high-end Öhlins forks and rear shock. The brakes came from Brembo’s top drawer: 320mm discs and radial-mounted four-piston four-pad calipers.

On the road, the 999 R is still a very seductive option. The engine is super-strong, but feels extremely relaxed, and is deceptively fast. Even flat out, the big V-twin feels like it’s barely above idle.

The 999 range only lasted a few years, before Ducati gave in and moved to the 1098 model in 2007, which had a much more ‘916’ design feel. The 1098 range was prettier, and took all the best tech from the 999 and 999 R. But hindsight and nostalgia gives the 999 a certain something in 2022.

It stands out from all the other pretty-boy Ducati twins, and especially in R or S form, is a fantastic thing to ride. Prices are on the rise, and there’s not a lot of them around, but get a good one, and you’ll have one of the best unsung Italian exotic superbikes ever made…

Ducati Desmosedici RR

If you want the most exotic sportsbike, then a MotoGP replica for the road has to be up at the top of the list. And that’s exactly what the Ducati Desmosedici was when it appeared in 2006.

It used a version of the firm’s MotoGP engine: a 989cc V-four DOHC engine with 16 desmodromic valves, gear-driven camshafts, titanium valves and conrods, sand-cast aluminium crankcases with sand-cast magnesium covers, cassette-type gearbox and 50mm Magneti Marelli throttle bodies. It made a claimed 200bhp@13,500rpm in a bike that weighed in at just 171kg dry, with the supplied race exhaust and ECU fitted. Those were stupendous numbers back then, and are not bad even now.

The chassis was packed with MotoGP-derived treats. The rear wheel was a then-fashionable 16” size, which wore a special 200/55 16 Bridgestone BT-01 tyre. The front forks were unique gas-charged Öhlins FG353 parts unavailable anywhere else, and the rear Öhlins shock had separate high and low speed damping adjustment.

Add in the unique forged magnesium Marchesini wheels, carbon fibre bodywork, 330mm front brake discs with radial mount Brembo monobloc race calipers, and you had the most special chassis around to go with that stupendous engine.

Indeed Ducati reckoned it was very similar to the GP6 racebike from 2006: the brakes, steel trellis frame, aluminium swingarm and wheels were all comparable to the GP components.

It cost £40,000 when it went on sale in 2007, and most bikes went straight into collectors’ heated garages. Plenty of folk rode theirs though – and the trackday seasons over the next couple of years in the UK saw more than one Desmosedici in the gravel.

Bizarrely, Ducati found itself on the receiving end of some grief from owners a few years later. As it turned out, the firm’s road-going V-twin superbikes soon started to rival the Desmosedici in terms of power and weight, The 1198R superbike launched in 2009 was lighter at 165kg dry, and made a claimed 180bhp in road trim – similar to what the Desmo produced without its race pipe and ECU fitted. And all at less than half the cost of the Desmosedici…

Most people were more than happy though. The Desmosedici RR was and is a one-off. Only Honda has sold anything similar, and its RC213V-S road-legal MotoGP replica was much more expensive with relatively poor performance as sold. The limited edition Desmosedicis are only going in one direction in terms of value, and it’s certainly earned its place in the pantheon of great Italian exotic superbikes.

Ducati Panigale V4 R

Ducati started calling its high-end sportsbikes after the factory’s home town of Borgo Panigale back in 2011, with the 1199 Panigale superbike. That was a V-twin, and its successor the 1299 was the last V-twin open-class superbike made by the firm. The Panigale moniker lived on though, applied to the firm’s latest superbike, the Panigale V4.

First launched in 2018 in 1,103cc form as the V4 and V4S, it used a road-tuned version of the company’s V4 MotoGP engine, with the 104cc extra capacity making up for the lower road tune, and giving an audacious 213bhp peak power. The 90° V-four motor used desmodromic valve operation, had DOHC four-valve heads, the latest ride-by-wire fuel injection, and Ducati’s very best electronic riding aids package.

This premier powertrain was housed in a chassis to match, especially in the V4S, which featured the Öhlins ECS semi-active suspension setup, using NPX forks and a TTX36 rear monoshock. Brakes were Brembo Stylema calipers and it all hung off a super-stiff steel tube trellis frame, with single-sided rear swingarm (the V4 used cheaper Showa suspension but kept the same power, electronics and brakes). Dry weight was just 173kg on the S, and it was a total riot to ride.

We’re here for the exotica though, and there are actually a few options on the V4 front. Ducati sold a Speciale version with high-end paint schemes and a Ducati Performance track package, that makes 223bhp. There’s also an SP version, with carbon fibre wheels and other track goodies – and a SuperLeggera version, with carbon frame, swingarm and wheels, titanium engine fasteners throughout, 224bhp power and 152.2kg dry mass, in track trim.

But the ultimate exotic V4 is arguably the V4 R. It’s a homologation special model, so uses a 999cc engine rather than the 1,103cc unit on the standard machines. That motor makes even more power though: a claimed 234bhp with the factory race kit. Dry mass is 165.5kg with the race kit, and it has a unique frame, fairing and suspension package.

The price for all this? £35,000 when new, and probably about the same used…

Mondial Piega

Of all the bikes we’ve mentioned here, this is perhaps the most niche. Mondial is a genuinely legendary Italian brand, which has no fewer than ten world championship titles to its name, all won between 1949 and 1957 (five riders’ and five manufacturers’ wins.) But it had declined massively in the 1960s and 70s, closing completely in 1979.

Twenty years later though, the brand returned with a new owner, wealthy businessman Roberto Ziletti. And its first new machine benefited from a historical association with Honda. Back in 1957, Mondial had sold Soichiro Honda one of its race bikes, and Honda returned the favour 45 years later, supplying its VTR1000/RC51 V-twin engine to Mondial for a new superbike design, the Mondial Piega (an almost unique step: Honda rarely allows other firms to use its powerplants.)

So, the fledgling Italian brand had a big help when starting out. The VTR engine was a top design, winning the WSBK title with Honda twice, in 2000 and 2002 – a 90° fuel injected, DOHC, eight-valve V-twin that put out a solid 133bhp. Mondial used its own exhaust, intake and injection setup, which gave a bit more grunt, up to a claimed 140bhp@9,800rpm.

The chassis was, of course, a piece of luscious exotica. Mondial made its own chrome-molybdenum steel tube trellis frame design, with a very trick rear swingarm. It looks like carbon fibre, but the main structure is another steel tube trellis component, with the carbon outer skin giving a racey look, while adding even more stiffness.

Front forks are by Paioli, and both front and rear suspension is fully adjustable. Brakes are Brembo Gold series calipers, with two-piece four-piston calipers up front. Bodywork is all carbon, with an optional carbon fuel tank, and dry weight is an impressive 179kg, 20kg less than the Honda SP1.

Riding the Mondial was the usual early-2000s Italian superbike experience, though improved over something like an MV Agusta F4 thanks to the well-developed Honda engine. The suspension was firm, the riding position uncompromising, and steering sharp. Its thoroughbred nature makes it a chore when you try to ride it slowly, but gets better as the speeds increase.

The V-twin engine was strong, though a little peakier than the gruntier Ducati superbikes of the time, and the underseat exhaust sounded glorious, as well as looking fabulous. The overall styling was a little bit controversial: there were question marks over the vertical stacked headlights which would be copied by Ducati’s 999 range a few years later.

The headlights aside though, the rest of the bike was a handsome beastie indeed: the classic blue and silver paint scheme matched up beautifully with the bare carbon fibre panels and gold-finished forks

MV Agusta F4

After designing something as legendary as the Ducati 916, you’d have thought that Massimo Tamburini would have struggled to come up with anything as beautiful. But just a few years after the 916 launched, the master of Italian bike design did it again, with the MV Agusta F4 750. A rather different-looking machine, and arguably not as gorgeous as the 916 head-on, but the F4 grabbed the imagination of the people, and put MV Agusta right back into the superbike game.

Under the sexy bodywork, the F4 was a serious piece of work. Rather than the typical Italian V-twin, it had an all-new inline four-cylinder motor, which was much more in tune with the historical Agusta range. Produced with help from Ferrari, the motor used a DOHC radial four valve per cylinder arrangement, with the pairs of inlet and exhaust valves slightly splayed out at the cam end, allowing a more efficient combustion chamber design, at the cost of more complexity in manufacture. Honda had tried this with its single-cylinder Dominator 650 engine, but it’s rare to see in multi-cylinder engines.

The engine was bolted into a composite steel tube/alloy forging frame design, with aluminium swingarm pivot plates on the basic F4, and magnesium parts on the high-end F4 Serie Oro version. A beautiful single-sided swingarm, again aluminium or magnesium depending on the version, echoed the 916 design, but had a very different look.

Brakes were bespoke Nissin race-type calipers, and suspension was by Showa and Sachs, while the special wheels came in forged magnesium on the Oro version and aluminium on the base bike.

The original 750cc F4 was a fabulous thing to ride on track, but it was hard work on the road. The riding position was extreme, with a lot of weight on the wrists, while the engine was a bit on the revvy side, with slightly fussy fuelling. There was a lot of heat to get rid of too, and together with the evocative underseat exhaust system, the F4 was hard work to ride slowly on hot days.

As with all 750cc fours in the 1990s though, it was the capacity choice which limited the appeal of the F4. It struggled to match much cheaper machinery like the Honda CBR900 RR FireBlade and Yamaha R1 in terms of power, and was harder to ride fast than the big V-twins from Ducati and Aprilia. The 750 limit was intended for race use of course, but few race teams were brave enough to use a fabulous exotic machine like the MV Agusta F4 as a hard-charging superbike racer.

The answer to all this came in 2005, when Agusta replaced the 750 F4 with a new 998cc F4 1000 version. It immediately produced 20bhp more than the 750 it replaced, with much more torque, and was a far faster road and track machine.

In terms of picking a favourite F4, you can go two ways – either plump for as original a 750 as you can – a Serie Oro or one of the Senna special editions would be a fabulous choice. On the other hand, for a bike to ride, the 1000s are much better. Go for one of the special editions – a Senna, Tamburini or Veltro, or the insane 190bhp 1100cc 312R model, with a top speed of 312 KPH (194mph)…